Into the Wild

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

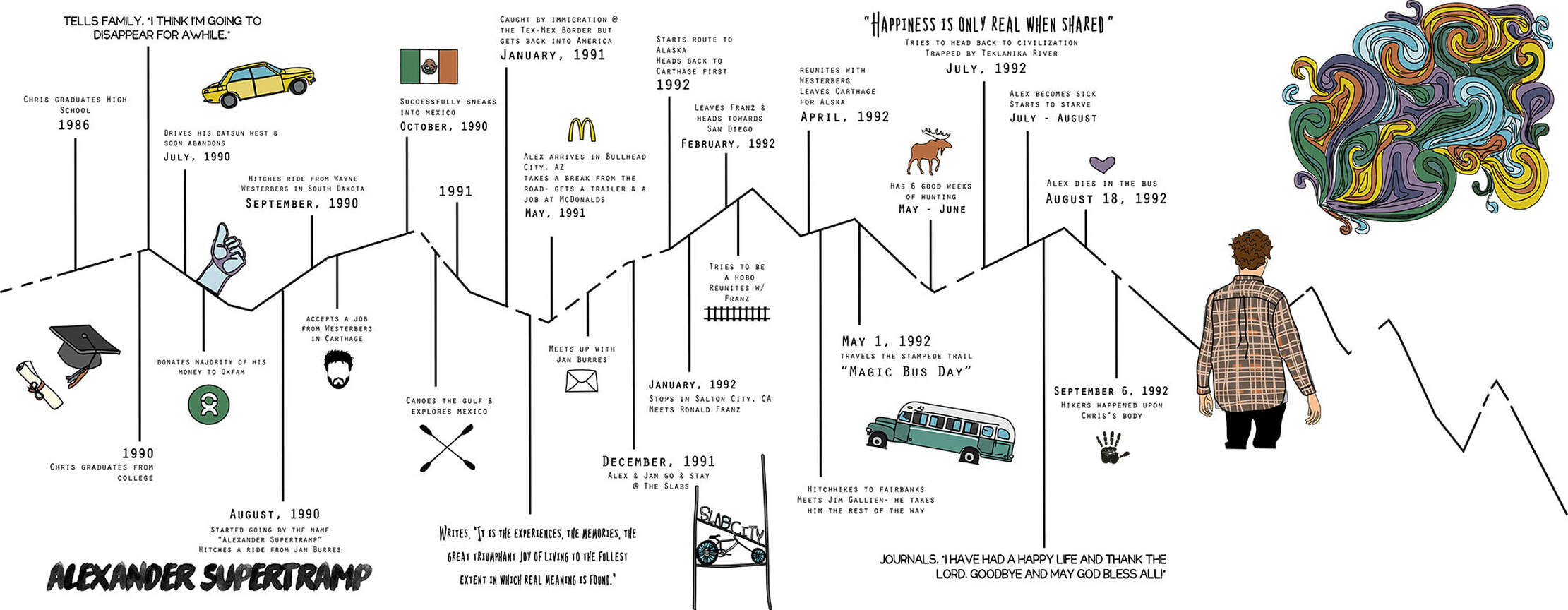

Timeline, source: http://www.rachelsweetdesign.com/into-the-wild.html

SUMMARY / REVIEW Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild provides a balanced account of how wilderness, risk, and romantic ideals captivate many youths, and it reveals the variety of reactions to those ideals. Its central figure, Chris McCandless—a kind, nature-loving young man—always resisted traditional rules. Inspired by literary figures like Thoreau, he graduated college and vanished from his family’s life. For nearly two years, he hitched around the western United States, living primarily in the wild, before tragically starving to death in the Alaskan wilderness due to accidental poisoning.

Krakauer, an experienced outdoorsman, focuses more on recounting events than offering philosophical commentary, though he does acknowledge his personal connection to McCandless. This approach keeps the narrative relatively objective while still exploring the implications of McCandless’s story.

PERSONAL CONTEXT I was drawn to this book after my own young urge to ditch town and everyone I knew, change my name, live nomadically and simply (though not necessarily in the wild). I wanted to escape the prison of having to live and die in a single life, one so mundane and inconsequential. I wanted to struggle, to reinvent myself, to learn, to be present, and to make connections and meaning. I wanted to experience life — the highs and lows — many times over. I, like many others, never pursued this but have come close. And now, I believe I have a responsibility to humanity that is difficult to ignore and will never end up doing this.

REFLECTION The widespread attention McCandless’s story has received stems partly from his premature death and the national media coverage that followed. In truth, a similar narrative might have surfaced with different details under a different name. Many strong reactions to McCandless reveal the ways readers project themselves onto him, either rejecting or empathizing with his choices.

Some critics harshly condemn McCandless as arrogant, selfish, and ill-prepared, and oddly some even docked the book’s rating for his perceived flaws as if it were written by Chris himself. Indeed, leaving his family in the dark was a harsh, almost criminal, act, and I suspect (and hope) he only intended to punish them before someday returning. However, I believe this was his only criminal act.

Despite these criticisms, I think many overlook McCandless’s fundamental motivation: he was searching for a pure, unencumbered life aligned with his ideals. It seems he was genuinely happy living on his own terms, and his journey wasn’t about flawless preparation or survival alone — he found meaning in self-reliance, discovery, and immersion in nature. Calling him “naive” or “foolish” reflects our own ideas about what a “good life” should look like. Yes, he made mistakes, and he bore their consequences. But to dismiss his quest because of its tragic end is to miss the point entirely. By embracing uncertainty, Chris lived the life he wanted — one shaped by his values, however different they may be from ours.

Likewise, those who label him unprepared or reckless forget that he lived this way for over a year and a half, hitchhiking around the American West, staying long stretches in the wilds, and surviving for months in the Alaskan bush. He studied local vegetation, carried a guide to edible plants, and recognized the potential danger. Could he have done more? Perhaps. But to say he should have wanted something else — like taking a plane instead of hitchhiking — ignores the reality that this was his chosen path. We may disagree with how he pursued his happiness, but we cannot sensibly reject the motivation and source of happiness itself. Telling him to dream differently is simply imposing our desires onto his. In that sense, criticizing Chris for his wants and motivations is missing the entire point of his journey.

I’ll finish by stealing this book quote from Matthew Ted’s comment:

The photo in this review is one of McCandless' final acts — one hand holding his final note toward the camera lens, the other raised in a brave, beatific farewell. Krakauer goes on to say this, of the photograph: But if he pitied himself in those last difficult hours—because he was so young, because he was alone, because his body had betrayed him and his will had let him down—it's not apparent from the photograph. He is smiling in the picture, and there is no mistaking the look in his eyes: Chris McCandless was at peace, serene as a monk gone to God. Or as McCandless once wrote of himself in the third person, But his spirit is soaring.